Spelling is intricately related to many literacy processes. Reading and spelling. Writing and spelling. We even see (sometimes misguided) connections between vocabulary and spelling practice. It is not easy to break apart spelling from other literacy work and in most cases we don’t want or need to. I started this blog out with a mini-series on reading aloud and since there are so many complicated areas related to spelling, spelling will get its own series here, too. I’ll start with early spelling development, which will focus quite a bit on the relationship between early reading and early writing and spelling and on invented spelling. The next part in the series will talk about how spelling develops alongside reading and some of the best practices for spelling instruction. This one is tricky, because you may find that your child isn’t learning in ways that coincide with what researchers tend to agree on for spelling instruction. This section will have to do with more isolated, skill-related, spelling practice. However, I think it is then important to bring us back to where we started with spelling in the context of writing, so this will be the final part in the series. I encourage questions or discussion of these ideas. I’d love to hear where your children are finding success or meeting with struggles. I’d love to hear what kind of spelling instruction is practiced at your child’s schools. Let’s talk about what’s going on and work together!

PART 1: Early Spelling and Invented Spelling

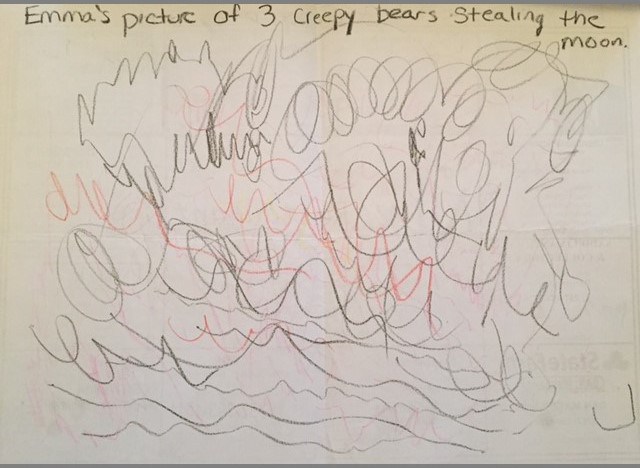

Spelling is related to reading and writing in inseparable ways, so you’ll see that it’s hard to talk about just one aspect with mentioning the others. In this way, it might seem like we are talking off-topic every now and then, but it’s only to bring us back to how these other processes – reading and writing – relate to development along with spelling. Early spelling practice grows from early writing, which includes scribbling, drawing, and early letter formation. Early literacy experts consider scribbling as the first stage of early writing. Why? Because writing is about communicating. Scribbling and drawing are a child’s first attempt to communicate. Here is a story written by my daughter on the back of a placemat from our favorite diner. At this stage, the process of creating the writing is most important. As she added color or layers of scribble she verbally added on to the story.

The next stage of early writing development is drawing that is more representational. Again, while we may not see the story by looking at the page after the fact, as children add pieces to their drawing they are adding to the layers and plot of the stories they are telling. In this next example, I first typed what Emma was telling me her story was about in scribbles (on another page). Then, I printed the words and she added the drawing.

Did I mention that reading, writing, and spelling are related? These were Emma’s words to her story, transcribed exactly as she said them. This piece actually highlights the importance of reading aloud. You can hear in her words, “She went far, all the way, always, to the great present place” that while this may not make a whole lot of sense, she is mimicking the “once upon a time in a land far away” story structure that she had heard in many of the stories we’d read aloud. Reading aloud gives students models for their own communication. (Oh, and don’t worry about the fact that the wicked king killed the princess. She was easily saved by the prince. She was also quick to forgive and later lived with the king happily until the mean dragon smashed her castle. There’s some plot holes, but she’s getting there.)

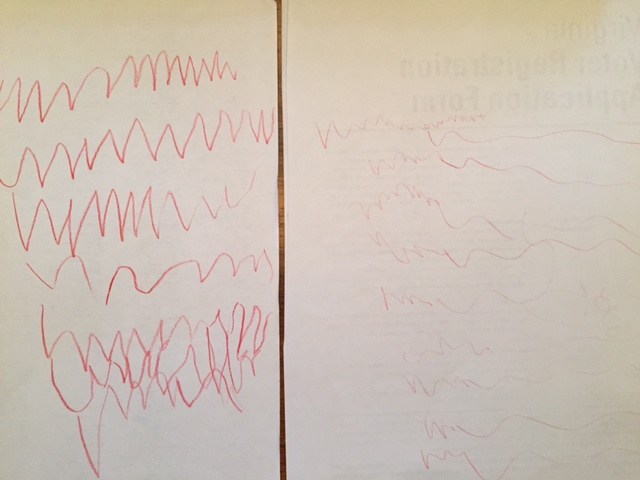

As children start to realize that the books they see have both words and pictures and they also see people writing and know what writing looks like, they move to a next stage of writing, even though they may not know any letters yet.

They often will copy the left to right motion that they see. You can see lines from top to bottom. They are doing their best representation of what they see in writing.

During this time, children are usually beginning to learn letters, as well. The next stage in their development is to put together strings of letters and shapes that resemble letters. (Sorry, I don’t have any diner place mats for this one!)

Then, finally, children start putting those letters together to form words. At this time, children are using their knowledge of the sounds of letters to decide which letters to use. They hear the word and match a letter to the sounds they hear. At first, they may focus mostly on consonant sounds and will likely skip the vowels as they form their words. When they do start including vowels, these are often letters that are incorrect because, let’s face it, there are a lot of confusing vowel patterns with standard English spelling. Let’s talk about some examples.

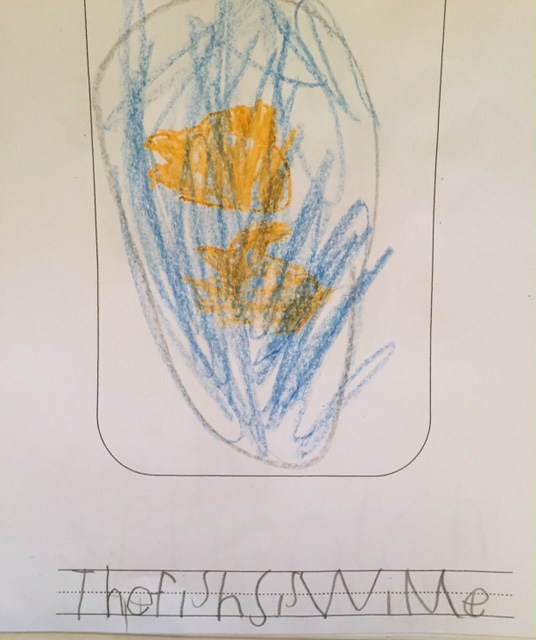

Thefishsiswime. The fishes is swimming. We can see that though Sam, (Emma’s little brother), had moved from letterlike strings to invented spelling, there is still a bit of the string of letters aspect as we have no spaces between words. However, there are some conventions he has learned here. He knows the word “the” and he knows the digraph – (two letters that make one sound)- /sh/. One of the difficulties of our language is that we don’t actually separate very much between words when we speak. We blend one word into the next. Children learning the language can tell more about when one word ends and another starts from the rise and fall of voices in word and sentence patterns, since they don’t hear individual words. (Try it out. Say a few sentences normally. Now say them trying to stop between each word. You sound like a robot, huh?) This is all to explain why there is one /s/ that ends the word “is” and starts the word “swim”. Because this is actually how children hear language. So, we have, “The fishs” (because, clearly, there’s more than one fish and he is overgeneralizing the rule for making a word plural), “iswime”. The last two words we already know share an /s/, so let’s separate that to “is swime”. Hearing all the sounds in swim is very well done. And it’s no wonder that there is no representation for /ing/. This is a very hard ending to figure out how to spell, so when listening for each sound, ‘swimming’, doesn’t sound all that different from “swimmy” to a young child’s ear. That /y/ sound at the end sounds like a long /e/, so using an “e” at the end is a good choice.

Now, that seems like a lot to think about for one sentence – The fishes is swimming. But this is the reason that invented spelling is not only a normal stage in developing swimming but a very important and informative stage. Children are exploring the sounds they know and experimenting with how to match those sounds to letters and put them into words. Spelling is an opposite process from reading words. Sounding out and reading words is called decoding, and spelling is called encoding. Letters are the code for words. And when we read we break the code and figure out what sounds those letters stand for and how they combine to words. When we spell, we figure out the sounds we want to put into code and choose the letters to represent them. By analyzing a young child’s invented spelling we can see which sounds they hear and can represent accurately with letters, and which they might not hear or at least not hear as clearly. We can watch as this develops and grows and teachers can use this information to know where to instruct them in phonemic awareness (individual sounds of our language) and phonics (matching sounds to letter) instruction.

We want children to feel very comfortable in this stage where they can explore and express themselves and use writing as a way to communicate. So, most of the time, we don’t need to spend any time trying to correct their spelling. Occasionally it might be appropriate to show them a conventional spelling with a friendly, “You did a really good job spelling this word; I can see how you heard all of those sounds and the letters that matched. You might have seen this word in your reading and it looked like this, [write conventional spelling], but I’m really proud of the writing you did here.” This lets them know that they did exactly what we wanted them to do in spelling the word on their own. Yet it also lets them see the conventional spelling and probably match it to when they’ve read the word in their reading. But we don’t want to place so much emphasis that kids sit in front of a paper and feel like they can’t write without asking the dreaded question, over and over, “How do you spell…?”

Now, eventually, children are transitioning from invented spelling to conventional spelling and as they start to know more words they do become more aware of whether what they are writing is spelled correctly. That’s when we do hear a lot more, “How do you spell…?” questions because kids have a greater desire to have their writing match the words that they know they’ve seen in reading. But we don’t want to discourage them from writing words they don’t know how to spell because we want them to feel free to communicate anything they wish through their writing. In other words, we don’t want them to feel limited to only writing words they know, because their thoughts are not limited to words they can spell. . This is something we want to encourage even as they start using more conventional spelling. Let’s see a few examples of what this transition might look like.

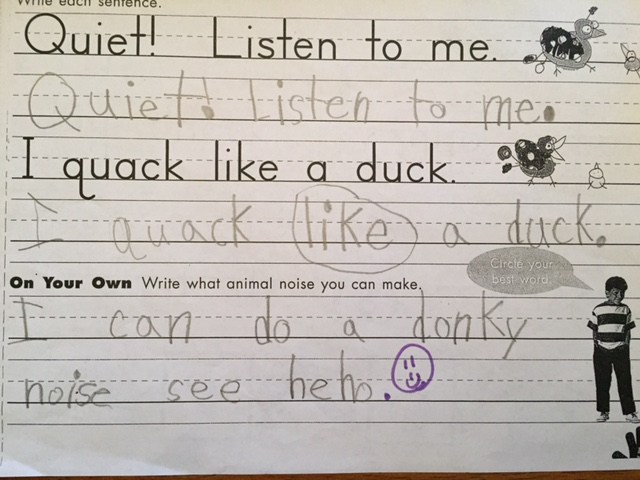

Here is one of Emma’s 1st grade examples. (The picture she drew is of her brother, saying “I am a monkey”, because it is obviously funny when your brother pretends to be a monkey). We can see that she is using some good patterns – /br/ to start brother. The digraph, /th/ in the middle of brother. She is missing the “e” in /er/ which is typical. She is also not aware of the doubling in “funny” but she has learned that words that sound like a long /e/ at the end often end in “y” so we are seeing that convention in her spelling.

Again, in this one we see the /y/ at the end of donkey, but she’s heard each of those sounds /d/ -/o/ – /n/- /k/- /e/ and represented each with a letter. We know there’s an “ey” at the end of donkey, but her spelling makes perfect sense given other rules she knows about words that end with that long e sound. Notice in the previous example, in the caption, “monke” is still spelled with an “e”, not a “y” so she wasn’t consistently using the y at that point, but was figuring out when it belonged with certain words. She did a great job in this donkey example with the word “noise”. The others were sight words – I, can, do, a, see – but “noise” she knew from reading, and could copy from the question (although children will do this much less than you think. They tend to forget that they have the correct spelling of a word right in front of them.) I love this example, also, because she adds a representation of the sound that she can make and so we see how she creates that sound using letters: “he ho” for what we might typically write as “hee haw”. This is a great example to see how she hears and represents sounds.

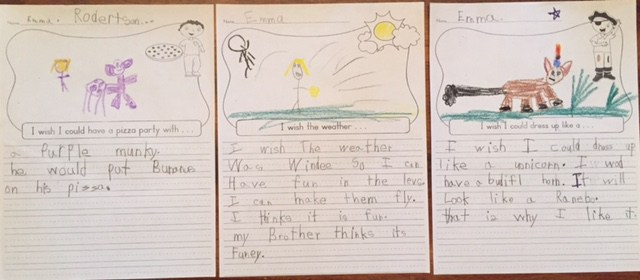

These last three examples are great writing examples that show a mixture of invented spelling and conventional spelling. It also highlights why it’s so important for kids to feel free to use invented spelling on words they don’t know. She wasn’t afraid to write what she really wanted to say, even if it wasn’t a word she’d learned how to spell. We want children to be able to express anything they want to communicate. These were all open ended prompts and she could, and did, write what she truly felt, not confined by spelling. Just for some background, we used to have a joke in our house that when something happened that no one took credit for “the purple monkeys” must have done it. Or when they doubted a reasonable answer I gave them, I would reframe it with a silly answer using “purple monkey” to show them that I really did mean my logical answer. Hence, a pizza party with purple monkeys.

The beauty in this is that it also gives educators a great window into understand the conventions she uses and understands and those she still needs to work on.

Take a look at these: munky, windee, funey – this tells us that, again, this is a convention that she’s trying to work out. She knows that sometimes it’s “y” and sometimes it’s “ey” so she tries them at different times.

And these: levs, uonicorn, ranebo. These each have (or don’t have) a vowel team (two vowels working together to make one sound). Leaves, unicorn, rainbow. She is using what she knows of letters to make these words. Leaves is missing it’s vowel team in her spelling, but she’s added a team to start unicorn (“uon”) thinking that she must need something more than just a ‘u’ to make the long u sound. In some of her other words (make, like) we see the silent e pattern, so it is not surprising that she used that pattern to make the rain (rane) in rainbow. And she’s seen words like “go” and “no” and so therefore it seemed plausible that the end of rainbow could be “bo” – “ranebo”. This spelling actually makes perfect sense and it helps us see that she understands silent e patterns and open syllable patterns (words that end in a long vowel sound using one and only one vowel).

It’s interesting to me that she correctly spells “could” multiple times in the unicorn piece, but used an invented spelling for “would”. So, she had remembered how to spell could using conventional spelling but not yet transferred that knowledge to it’s pair “would”. (We do see it correctly in the purple monkey pizza party writing. This may be because these pieces are out of order – or it may be that she just wasn’t consistent yet with her use of this spelling).

Overall, her explorations and errors let us see what she understands and uses consistently, what she’s developing and understanding of, and what to work on next.

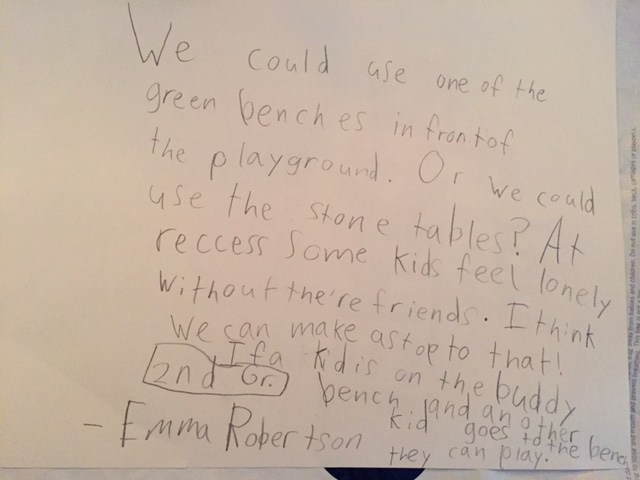

And why is this so important? Because writing is powerful communicating. Writing lets children make change in the world. So, we need to let them explore, let them experiment, and let them feel free to write without always being confined by “correct” or conventional spelling. Writing (at this age) is no less powerful with a few unconventional spellings.

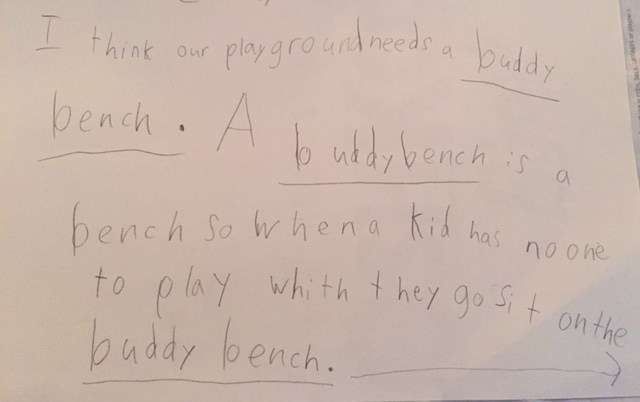

Emma, 2nd grade, letter to principal to institute the use of a buddy bench on their school playground.

As always, please comment and ask any questions you have! What have you seen in your child’s writing? Do you see their writing differently now than you did before? Do you still have concerns about their writing?

Look out in the coming days for the next two parts to this series on spelling as we move through spelling development and instruction and then link back to writing one last time and talk about some of the struggles for writing and spelling for older grade children.

Thanks for joining me! Let me know you were here by commenting or by following my blog!